Hazy Osterwald, born Rolf Erich Osterwalder in 1922, started playing the piano at 8 years old although at first it was not an instrument he was comfortable with. Taking after his father, a popular football player in Bern, he was far more interested in sports than in music. But it was the music which would later make him world famous. It was during his high school years in Bern when he heard a school band playing jazz that the sparks started to fly and never stopped. Soon after, he was the leader of the band, he worked as an arranger, a pianist and later also as a trumpet player for Fred Böhler. He met Teddy Stauffer (also known as „Mr. Acapulco“), founded his own orchestra and taught himself to be an excellent vibraphonist. The foundation for his later success was laid and he became a star. He appeared in several films and shows, worked with people such as Peter Alexander, Joachim Kuhlenkampf, Peter Frankenfeld and met some of the greatest musicians in the world. In his interview with Christian Dueblin Hazy Osterwald speaks about the beginnings of his career, about his love of jazz and about the changes in music during and after the Second World War.

Dueblin: Mr. Osterwald, it took some time for you to develop a passion for music. You didn’t really enjoy your first years as a piano student. Given that you later became a legendary and famous musician, how do you explain this?

Hazy Osterwald: My mother wanted me to become a trained classical pianist. At 8 I started my first piano lessons. My father was an international football player and I was also very interested in that sport, more so than in piano playing. My piano lessons with Miss Piel were, therefore, not very successful. When I was 11, Miss Piel spoke to my mother and said she had tried everything but I just didn’t enjoy playing the piano. Further lessons just didn’t make sense. I was really only playing it to please my mother. The same was true for my late sister.

Dueblin: What finally sparked your enthusiasm for music?

Hazy Osterwald: I went to high school in Bern and one day I heard a small orchestra playing. I was maybe 14 years old then. I liked the music a lot; the young musicians played some jazz numbers. The orchestra was made up of only an accordion, a saxophone and trumpet, a drum set and a guitar. I applied as a pianist in the music group and was invited to audition. Afterwards they told me that my piano playing wasn’t good enough but they gave me four months to practice before auditioning again. I went home immediately and practised for hours and days on end. It was clear to me that jazz was my music. I was infected with the „Jazz-Virus“.

The trumpet player in this orchestra – his name was Haldemann – had an older brother who was studying in England and who brought the newest albums from the USA and England to Switzerland. The jazz albums inspired and excited me enormously. These were the newest hits, that were slowly becoming known in Switzerland. By listening to these albums, I learned the tunes and started writing them down on paper. I made great progress in a short time. Haldemann’s brother invited me to his house and showed me tricks on the piano and also helped me in the beginning with writing the notes. I was inspired everywhere and absorbed everything I listened to.

Dueblin: I expect your mother was very surprised at your sudden assiduity on the long neglected piano…

Hazy Osterwald: (Laughs) I drove everyone around me crazy with my piano practising. No one in my family or in the house was used to it. I was very motivated, also because of the competition: another person who was also asked to come back for a second audition. After four months I auditioned again and the orchestra chose me. After a year I had become the leader of the orchestra. At the high school ball we had the opportunity to play in front of the other students. After the concert I was ordered to the principal, Mr. Burri’s, office. He made it clear to me that it was forbidden at the school to charge for our performances and to make money with our music. I tried to explain that we weren’t playing for money but we were asking for donations for a new contrabass that we really needed. It didn’t do any good. He said that if we ever played for money again we would be suspended. He meant it and the message came through loud and clear to me. I was afraid to play for money. That was in 1938. I told myself though that the principal could not forbid me from writing music and arrangements and I looked up Fred Böhler who, at the time along with Teddy Stauffer, was the most famous bandleader in Switzerland.

Black Clan Orchestra, Alhambra Bern

Dueblin: How did you first make contact with the legendary Fred Böhler and his orchestra?

Hazy Osterwald: There was a popular nightclub in Bern at that time: the „Chikito“, where many of the greats from the Jazz and easy listening scene played. At one of his performances in the Chikito, I asked Fred Böhler if I could write an arrangement for him. Afterwards I wrote the arrangement for the jazz standard „Rosetta“ and brought it to him as a reference. The musicians were thrilled with my amateurish arrangement. Fred Böhler told me I could continue writing for them and from then on paid me 5 francs per arrangement. This solved quite a few of my financial worries. I soon realised that the piano at that time was an unrewarding instrument. The high quality, mobile pianos didn’t exist then and you always played facing the wall with your back to the audience. That’s why I bought a trumpet. It cost me 20 francs at the time and I started to teach myself to play

People always told me I could play the piano well. I played in suburbian bands from Bern, but, after the warning from the principal, I always had to wear a false moustache so no one would recognise me (laughs). At some point Fred Böhler asked me if, in addition to writing the arrangements, I would also work for him as a pianist. He wanted to put together a bigger orchestra. He had 9 musicians in his band, played the piano himself and needed a pianist, so that he could also take breaks. The other musicians always traded off at the breaks. At that time the band played several hours per day. Of course I was excited by his offer, but I told him I had to pass the university entrance exams.

My father had warned me that he would send me to work in a factory if I didn’t pass. Shortly before the exams, he sent me to the country to a friend who owned a restaurant. The restaurant had a piano and he said I should prepare for the exam there and only play the piano after I had finished my homework. I followed his advice and passed the exams. As he presented me with my diploma, the principal announced in front of all the gathered students “Osterwalder got lucky!” (laughs).

Hazy Osterwald and his colleagues

Dueblin: What did you do after graduation?

Hazy Osterwald: In 1941 I received my attestation for the successful exam results. I was given the diploma at 11:00 am. The same day at 4pm, I was scheduled to play with Fred Böhler and his orchestra in Lausanne. I drove directly to Lausanne, played the piano during the breaks and also played the trumpet.

Dueblin: You learned a new instrument so quickly and so well that you could play with the best orchestra in Switzerland?! How did you do it?

Hazy Osterwald: (Laughs) I wasn’t really that good on the trumpet back then. The first trumpet player in the orchestra told me at the time “Osterwald you play miserably!” Fred Böhler however, was taken with my piano playing and my commitment to the orchestra and to the music and wanted to keep me on at all costs. We played nights on end. We also played in the afternoons and people danced to our music. Then I was called up for military service and had to go Dübendorf during the war. The basic training was very hard due to the war. The German army was a model for discipline and military obedience in the Swiss army. I managed again and again, however, to leave the army to play as a musician, but I always had to go back.

In the military school we had every Sunday off. We often went to see Teddy Stauffer in Zürich. Because of the war, he had stayed in Switzerland with his orchestra. After basic training, I went back to Fred Böhler in the band, but he couldn’t keep me on because I always had to do military service.

In 1944 I wanted to put together my own orchestra and my plans were quite advanced. I kept getting called up for military service, though, and I knew that my orchestra would not be successful if I had to keep cancelling gigs. I was devastated. At that time I was playing with the Teddies and as I was walking down the Bahnhofstrasse in Zürich, I saw a sign for an orthopaedic doctor. I thought about it for a while and soon after went into the clinic. A doctor in military uniform opened the door and asked me to come in. I explained to him that I was having problems with my flat feet. He examined me and wrote me an attestation. With this, I went in front of a military court of inquiry and was assigned to civil service. That was my musical salvation (laughs).

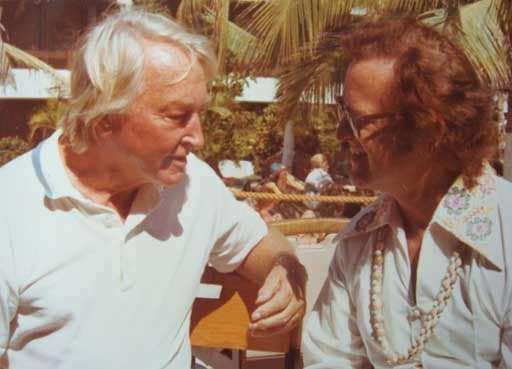

Teddy Stauffer and Hazy Osterwald

Dueblin: Teddy Stauffer was already quite famous internationally. He later married the actress Hedy Lamarr and was also romantically involved with Rita Hayworth. How did you meet this music and orchestra legend?

Hazy Osterwald: While I was in high school, Teddy Stauffer had a concert in Bern. I was impressed by him. In Germany, most of the best choir masters were Jews who were then hunted down and later killed. The Nazi regime was looking for Arians. Teddy Stauffer was a tall, blonde man — the embodiment of a non-Jew. He was, therefore, called to Germany, where he founded a Big Band and played for years. He was, however, no friend of the Nazis. In 1939 he came to Zürich for the National Exhibition and I left my class and went to see him at the „Thé Dansant“-Spielen“ . Every high school class was allowed to go to the National Exhibition. I introduced myself to Teddy as a musician and Berner. We spoke for a long time and he took me to meet his musicians – all professionals with a lot of experience. Even during the military school, I could always go listen to him play. He was the one who inspired me to learn the trumpet. It’s a coveted instrument and with it, you will always find work. As I joined the “Teddies“, Teddy Stauffer was already in the USA. He was pleased with my talent and my enthusiasm and was a sort of mentor for me. Many years later when I went to the USA, I visited him in Mexico. He had settled in Acapulco. I visited him a total of six times there.

Later I founded my own orchestra. Colonel Eugen Tripet, a high military officer, was the owner of the Chikito in Bern. I called on him and asked him if he’d give me a chance to play at the Chikito. I explained to him that I wanted to create my own orchestra but I needed an engagement to put my plan into action. He gave me a funny look and was sceptical, but his brother-in-law and his wife liked my idea and I got the engagement in the Chikito with my own orchestra founded in 1944. The orchestra had 9 members. The stage was full of flowers on our first evening. They were for me and our singer. It was a wonderful time that I enjoy thinking back on. Jazz was very popular and Eugen Tripet was quite satisfied because the night club was always full.

Hazy Osterwald and Kitty Ramon, Chikita Bern

Dueblin: The singer was Kitty Ramon, at the time a popular artist in the Swiss music scene. She came from the Netherlands.

Hazy Osterwald: She had worked during the war for Fred Böhler in his orchestra. I asked her if she would sing for me. She didn’t know too many people then and agreed. Later she wasn’t allowed to perform in the Chikito anymore. Tripet warned her not to hang out with the American soldiers that came to the bar on leave. Kitty Ramon was a bit of a difficult character. She would only sing for a short time, and then sit at the table with the Americans which enraged Tripet. She didn’t pay any attention to him and Colonel Tripet threw her out. I had to accept that and wanted to stay. I didn’t have another job as a musician. Later I worked with a Greek singer named Kay Linn, who lived in Switzerland during the war. During this time I quickly became popular. My band was called the „Hazy Osterwald Orchestra“.

Dueblin: That was also a difficult time, however. Many musicians from popular orchestras had to leave Switzerland during the war or wanted to go back to their families. A lot of bands broke up.

Hazy Osterwald: That’s true. A lot of musicians wanted to go home, others had to leave the country, and still others were able to stay in Switzerland. This created a huge vacuum of musicians in Switzerland. The Swiss musicians profited from this situation because suddenly there were openings everywhere for musicians.

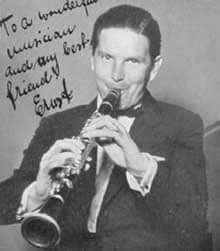

Ernst Höllerhagen

Dueblin: An important musician who was able to stay in Switzerland at that time was Ernst Höllerhagen. He was considered extremely talented. It has been said that he bid farewell to a Gestapo officer who wanted to forbid jazz music with „Heil Benny Goodman“.

Hazy Osterwald: That wasn’t exactly true. Höllerhagen was truly one of the best musicians of that time. The Nazis frowned on jazz and declared it decadent. Höllerhagen was in Teddy Stauffer’s orchestra the „Original Teddies“ and came with him from Germany to Switzerland. He stayed here in contrast to many musicians from the orchestra who went home during the war. He had a girlfriend in England that he always visited. And now to your anecdote: the musicians who played in Germany at the time liked to make fun of the Nazis. I only know that they always raised their hand and shouted “3 Liters” instead of “Heil Hitler” (laughs). He never told me the anecdote with „Heil Benny Goodman“ but he was imprisoned for several days because of a similar joke. He was a musician in my orchestra for a long time and we were good friends.

He had a facial paralysis and sometimes couldn’t play the clarinet. During these periods he played the violin a lot. Only a few people knew of this other passion of Höllerhagen’s. I admired him as a musician and we travelled all over Europe together. Once while on tour in Copenhagen, Benny Goodman and his band suddenly came into the club where we were playing. Your interview-partner Dick Hyman was also there with us and I met this amazing pianist there for the first time. Höllerhagen was with us on stage and played brilliantly as usual. Benny Goodman turned his back on his own people and table and listened attentively to our concert, which he clearly enjoyed. He came up to us and told Höllerhagen, that he had never heard such a talented clarinettist in Europe and congratulated him. That was a tremendous compliment, not only for Höllerhagen, but also for me and the whole orchestra. The paralysis symptoms eventually got better, but they came back and, in 1956, Höllerhagen took his own life in a hotel room in Interlaken, Switzerland. The suicide was directly related to his illness. It was rumoured that he killed himself over a girl, but I don’t believe that. I don’t know who that girl should have been.

Dueblin: Who inspired you at the time? Did you have idols who you admired and respected?

Hazy Osterwald: I was so young and didn’t know that many. Stride Piano, as you play it was already old- fashioned for us then. I admired Benny Goodman and Lionel Hampton. I found his vibraphone-playing brilliant. Fred Böhler had a first-class clarinettist and saxophonist named Glyn Paque. He was a black man who came to Switzerland in 1939. He always asked me if I didn’t want to play the vibraphone, which I finally did. Then came the time that I enlarged my orchestra to 12 members, but I couldn’t leave the country because of the war. After the war, there wasn’t a country who could engage and pay for a jazz orchestra. So we were forced to travel between Geneva, Zürich, Bern and Basel to play.

Hazy Osterwald and Big Band, Moulin Rouge Geneva, 1948

Dueblin: That was the time of the Moulin Rouge in Geneva, the Odeon in Basel and the Chikito in Bern, to name just a few of the trend clubs. You went to Germany after the difficult post-war time and became popular stars. Why did you go to Germany

Hazy Osterwald: Switzerland is small and I knew it well. I had always wanted to go abroad. Before I went to Germany and became famous there, I was in Holland, Belgium, Sweden, England and also in Austria. I didn’t get a work permit to go to the USA. Germany realised that they had made a mistake with the Nazis. We didn’t hold a grudge and even went to the German television. The German director Michael Pfleghar asked us in the Kulm-Hotel in Arosa if we would like to do a television job in Stuttgart. I was offered more and more opportunities in Germany. The pay was very good. It was always said that the Swiss television and radio was jealous of me, and it’s true that they never played me. I was already world-famous but I never got offers from Swiss radio or television. I have never really understood it. Today I can laugh about it, but that the time it was difficult for me.

Dueblin: Why do you think it was that the broadcasting companies in Switzerland ignored you so?

Hazy Osterwald: It’s difficult to say. I think that it is a characteristic peculiarity of the Swiss to be always somewhat jealous and begrudging: it’s still true today. One is always sceptical of stars or would-be stars and it’s almost as if they are waiting for them to fail. In the other countries that I worked, it was, and still is, completely different. In Germany, for example, they were happy to have a new star who could entertain people with good music. Even today I’m played very rarely in Switzerland. When I mentioned this to Max Ernst, the boss of Swiss television at the time, he told me to my face: „Well, you play in Germany and we don’t need you in Switzerland.”

Dueblin: Was this Swiss diffidence possibly one of the reasons why Teddy Stauffer went back to Germany, then later to the USA and finally to Mexico?

Hazy Osterwald: Teddy Stauffer became famous in the time before television. For me it was different. I got famous exactly at the time that television was starting to bloom and become increasingly important. Teddy really enjoyed going abroad. Also he would have had to do military duty, which he didn’t want. In Acapulco he told me a lot abut his business and activities. I think it was his love of other countries which led him abroad. Teddy was first hired as a ski instructor in the USA. When his work permit expired, he went to Mexico to renew his visa there. They refused him however. The Americans accused him of being too long in Berlin as the Nazis were in power. He settled in Mexico.

Dueblin: You hired the best musicians and your music is pure and technically perfect. This is true too for Teddy Stauffer und Fred Böhler’s music. In terms of music quality, were they role models for you?

Hazy Osterwald: It is interesting after all these years to look back and see which music lasted and which didn’t. In my opinion, Beat and Rock will not stand the test of time. Jazz in general, Stride Piano, that we spoke about, or Ragtime, will always be listened to: perhaps by only a few people, but this type of music is eternal. Jazz will never disappear like other music styles. A lot of music is cheap and not worth much. Dixieland is also a style that will remain and stand the test of time. It’s a bit like football: football is a sport that is challenging and moves in a direction that is enduring. People will still play it in 100 years.

Dueblin: How would you define your standards for music?

Hazy Osterwald: For me, superior music means that the melody, tune and rhythm have to be right. These are the three foundation pillars of music. I think that tune and melody alone, as is common in classical music, isn’t enough. This is only my personal opinion and really a question of taste. Still today, more people listen to classical music than to jazz. The folk music which has become popular in the last 10 to 15 years is cheap music, in my opinion. It won’t last because it is usually not discriminating and one of the foundation pillars is often missing or imperfect.

Dueblin: Were you also acquainted with the late musician Artur Beul? He was also very famous in the fifties and sixties with his folk music.

Hazy Osterwald: We were friends. He was no jazz musician but we played his „Nach em Räge schint d’Sunne“. He was a very good popular composer. That was his musical home. He created more good popular compositions than one could have imagined, and he served big stars with his music. He was ambitious his whole life long. For me, however, it was always jazz that inspired me.

Hazy Osterwald and Miss Regency Palace, Hyatt Regency Beach Palace

Dueblin: In 1958 riots and chaos broke out at a Billy Haley concert in Berlin. The concert had to be ended prematurely. This new music seemed to make people crazy, as was the case with Beatles concerts later. How do you remember the coming of Rock’n Roll in Europe and what consequences did it have for you, your work and jazz?

Hazy Osterwald: At that time I was in Stockholm. A friend of mine came back from the USA and we met up in Sweden. He had Billy Haley albums with him. As I listened to this music for the first time, it was clear to me that Rock’n Roll was the future. I was somewhat afraid to play this music, though. I thought that this music would get very big and then fall apart again. It didn’t turn out quite as bad as I had feared, but I was right to a certain degree. Even Rock’n Roll was replaced and has sunk. It lasted a lot longer than I thought, though. I decided to stay loyal to jazz and not follow this new style. When I married and had children, I took on a lot of gigs, not only jazz-engagements.

I had to earn money for me, my family and the orchestra. But jazz was always dearest to me. There were no sponsors for musicians at that time, as there are today. The musicians had to earn their money themselves as businessmen. Jazz musicians and jazz orchestras had an advantage in the fight for gigs. They were able to play rhythmically perfect. It was a characteristic that was demanded by radio, television and film and classical musicians couldn’t do it, or at least not as well.

Dueblin: Obviously you could do it and offered what the radio, television and film industry wanted. You became a popular star in Germany. How do you explain this unbelievable success in our neighbouring country and also worldwide?

Hazy Osterwald: I gave thousands of concerts and played in about 15 German-speaking films. I remember fondly back on this time with Joachim Kuhlenkampf, Peter Frankenfeld, Peter Alexander and so many others. They were brilliant people and it was a brilliant time. You mentioned Germany specifically. It is a very musical country, more so than Switzerland. It was thus easy for me to get into the German musical scene and inspire the people. We had our political reservations because of the Second World War and, in the beginning, we cancelled several engagements. Later, we received film offers, which we took. I maintained many friendships and met everyone who was anyone, or who would be. For example, as he was still very young, I showed Udo Jürgens how he should stand on the stage. It was clear to me even then that he would become a star. It has made me very happy following his career, supporting it and being a part of it.

Hazy Osterwald and Christian Dueblin

Dueblin: You have stopped playing and your health is impaired. You suffer from Parkinson’s. What do you wish for the future?

Hazy Osterwald: I can’t wish for much. I am 88 and I’m coming to the end, really. I don’t think about it though. I’m in good spirits and look forward to all the beautiful things to come and I’m happy to have a wonderful woman at my side. I am also, however, a bit sad when I see that the world really hasn’t got better. We made fun of the greediness of people at that time in „Konjunktur Cha Cha“. In addition to the many good things that came from America, we also took on the bad, and only a few people seem to see the problems with this. In America, money is more important than it is here. Even in my time that was the case. But now we’ve started to make money the most central and important thing in our lives, too. This financial crisis can’t be explained any other way. I wish that more people would listen to and play music. That is much more valuable than simple money.

Dueblin: Mr. Osterwald thank you very much for this conversation. I wish you and your wife all the best and good health.

Translation from German into English by Andrea Dannegger, Allschwil. (C) 2010 by Christian Dueblin. All rights reserved. Other publications require the author’s explicit consent.

______________________________

Links

– on last.fm

– on iTunes

– Wikipedia (German)

More interviews about piano music and composing – with pianists and other musicians:

- Jon Lord about composing, his music career and the developments in the music industry

- Chi Coltrane about her comeback, about other music legends and the secrets of the music business

- Nicki Parrott about her love for Jazz, her career, music legend Les Paul and the significance of musical mentors for young talents

- Dick Hyman about playing the piano, jazz and life

- Giovanni Antonini about his musical career, authentic performance practice and his approach to conducting