Kaspar M. Fleischmann, born in 1945, is one of the most renowned photo gallery owners and photography collectors in the world today. In 1979, he founded the Zur Stockeregg gallery in Zurich, Switzerland and, with the establishment of the photography sector of ART Basel and as co-initiator of the Photography Show New York and Paris Photo, has set milestones in photographic art. Fleischmann, Economist (licentiatus oeconomiae, University of St. Gallen in Switzerland) and Ethnologist (licentiatus philosophiae), has also dealt with photography from a scientific perspective throughout his life. In addition to making major donations of photographic art to the Kunsthaus Zürich and Fotomuseum Winterthur, in 2006 Kaspar M. Fleischmann, through the Dr. Carlo Fleischmann Foundation, made possible a professorship in the „Theory and History of Photography“ at the University of Zurich. In his conversation with Christian Dueblin, he describes the origins of the Dr. Carlo Fleischmann Foundation, the beginnings of photography, photography as an art form, the age of digital cameras and talks of his vision and goals for photographic art in Switzerland.

Dueblin: Mr. Fleischmann, the Dr. Carlo Fleischmann Foundation has, for decades, been committed to supporting projects in the areas of art, culture, education and science. Please tell us about your uncle, Dr. Carlo Fleischmann?

Kaspar M. Fleischmann: Dr. Carlo Fleischmann was one of my father’s three brothers. After the death of my grandfather, Michael Fleischmann, he, as the eldest brother, took over the management of the former Fleischmann & Co, a company principally trading in grain, and quite successful in the import and export of raw materials. In the late 1950s, Dr. Fleischmann decided to invest a considerable amount of money into a foundation which he had established to provide financial support for art, culture and education in Switzerland. Since it’s formation, a multitude of larger and smaller projects have been financially supported.

Dr. Fleischmann always personally evaluated applicants and their projects and decided whether to donate money from the foundation or not. When I joined the foundation board in 1974, I wanted to keep up with the times and bring in more vitality. My goal was to consider a greater number of applicants and support these with small or medium sums of money. As long as the applicants respected the guidelines and met the expected standards, as a general rule I let them know that they could count on that sum every year. In this way, the foundation provided annual support to the Neumarkt theatre in Zurich, for example. The concept proved successful and over recent decades we have thus been able to financially support and enable the realisation of hundreds of smaller projects. In addition, we have also always had enough money to support two or three major projects each year. For example we donated the polar bears to the Zurich Zoo a few years ago, given repeated grants to the Rietberg Museum for acquisitions, made donations to special schools for specific projects and much more.

About four years ago, I decided, together with the board, to make another radical change. This arose out of personal reasons and had to be both sustainable and in the interest of the founder. We split the foundation and its capital into two divisions. One covers art and culture and the other science and education. With the first division, we supported the Kunsthaus Zürich, donating rare photo collages (photoplasticen and photo montages) by Herbert Bayer. The second division went to the Zurich University where, since 2007, the Art History Institute has conducted a course of study in the “Theory and History of Photography”. The foundation as a whole has been transferred to the University of Zurich and is now exclusively committed to promoting all aspects of photography. Now one can earn a Bachelor’s, Master’s and PhD degree in the field of photography following the Bologna System. The ultimate aim is a professorship.

Dueblin: What motivated your uncle in the 1950s to allocate a large sum of money for cultural purposes?

My uncle was a very well-educated and sophisticated entrepreneur with comprehensive views. He felt, unlike most managers of today, that entrepreneurship brings with it social and cultural responsibilities. In his daily life, there was an interaction between business and culture which was important to him and which he cultivated. He was keenly interested in philosophical questions and literature. Art in general accompanied him throughout his life. His aim was to make a cultural contribution to Switzerland. Since he had earned a great deal of money, he wanted to offer something in return to Switzerland.

Dueblin: Mr. Fleischmann, you have been considerably involved in art and culture. In 1979 you opened one of Europe’s first photo galleries in Zurich, and you were fundamentally responsible for firmly establishing photography in the art world of Switzerland and Europe. Why did it take Europe decades longer than the USA to recognise photography as an art form in its own right?

The answer is simple. The USA and photography are almost the same age. In the USA, photography is classified under „Visual Arts“. Every major museum in the USA exhibits photographic art and it has held a fixed place in museums for decades. Visual arts in the USA comprises painting, prints, lithography, video art and also photography. There has never been discrimination of any kind. In Europe, the situation has been quite different. With thousands of years of art history, photography was neglected: seen mainly as a means of providing information for papers, magazines and advertising columns. For decades this conservative attitude made it impossible to establish photography as an art form. This mindset was one of the biggest hurdles that I have had to overcome in my now thirty year commitment to photography. It took years of work to convey the significance of photography.

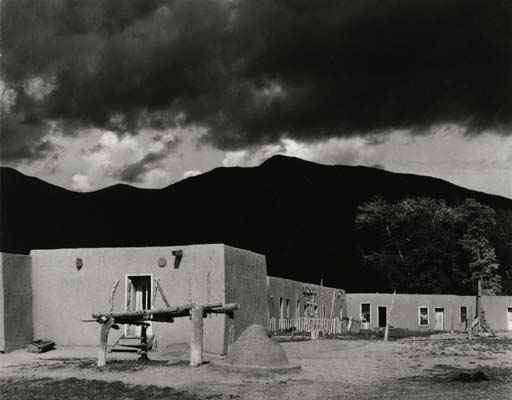

Paul Strand: „Black mountain“, Cerro, New Mexico, 1932, Vintage gelatin silver print (c) Galerie zur Stockeregg, Zürich, Kaspar M. Fleischmann

Dueblin: In your opinion, how significant is Alfred Stieglitz, the well-known photographer and photo gallery pioneer, to photography?

Seen from the perspective of photographic and intellectual history, Alfred Stieglitz is indispensable; a key figure in the world of photography. Early on, he surrounded himself with incredibly talented photographers, most notably Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. This trio wrote photographic history and, to this day, have had enormous importance in photographic art. Stieglitz had a vision. He wanted to establish photography as an art form on a par with other art genres.

He, himself, was an incredibly good photographer, and he used photography very early on as a medium for artistic expression. In 1903, he founded the legendary “Gallery 291” at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York. He was married to Georgia O’Keeffe, who was at that time already a well-known painter. He began to exhibit photography in his gallery, surrounded by sculptures, paintings, lithography, prints and architectural drawings. Literature also played a major role in his gallery and it was frequented by many renowned writers. With this type of interdisciplinary exhibition, together with his cybernetic approach, he was able to bring photographic art to a wider public in the USA. He wanted everyone to understand that photography is something special. Without a doubt, he achieved this goal. As early as 1918, photography in the USA was well-established as an autonomous art form.

Stieglitz sent Steichen to Europe with the task of integrating the best painters into his gallery’s photo exhibitions. He had taken Strand on board because he was exceptionally talented, and Stieglitz saw that Strand was able to bring the physical reprint to such perfection that it became a monument. Their powerful combination of art and skill was groundbreaking. Stieglitz then published the magazine “Camera Work”, which is today one of the most important sources of information about the history of photography. The most interesting pictures were printed in that magazine in fantastic quality. Several texts by famous writers were also featured in the magazine.

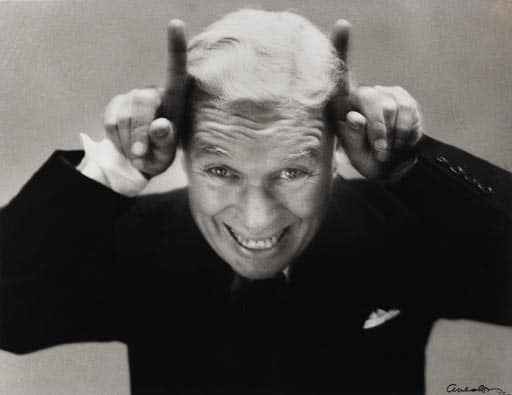

Richard Avedon: „Charlie Chaplin Leaving America“, New York, 1952, Vintage gelatin silver print (c) Galerie zur Stockeregg, Zürich, Kaspar M. Fleischmann

Dueblin: Do you see yourself as a sort of Stieglitz in Europe? Was he a role model for you?

At a time when photography was not an accepted art form in Switzerland, I opened a photographic art gallery in Zurich. In those days, many people shook their heads and did not understand me. For the opening exhibition, I deliberately chose Ansel Adams, whose fantastic landscape prints could attract attention. Today he is a respected classic photographer whose landscapes sell for substantial prices. His landscape photography of the High Sierras actually secured the protection of certain areas of the USA as nature reserves. His message had political impact. Also in the laboratory, he was a meticulous artist. The expression “The negative is the score and the print is its performance” came from him.The “performance” was, for him, what you make from the negative in a laboratory. He was originally a musician but was attracted by nature and tried to capture it with his photos. His pictures, thus, can be seen as musical interpretations of nature. You need no special knowledge of photography to understand his pictures. This is why Ansel Adams was the best entry into the gallery business for me. The world’s most expensive photo at that time, taken by Ansel Adams, cost US$20,000. The press was interested in this photo and, therefore, came to the gallery. Many journalists, not very knowledgeable about photography, thought that you could make an endless number of identical reprints from a negative. There were even people who, when they saw the high prices of certain photographs, spoke of “extortion”. The NZZ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung) reported that anyone who went to my photo gallery to see the exhibition would at least see nice frames. So, as you can imagine, the first years were not very easy.

Dueblin: What was so special about this most expensive photograph that you offered in your gallery?

The title of the photo was “Moonrise Hernandez”. It was the scene of a cemetery with the moon rising in the background. Technically this photo was a marvel as one could not explain how someone could have produced something so perfect. “Moonrise Hernandez” by Ansel Adams can be seen in many museums which show photography and is one of the most important landscape photos of all time.

Dueblin: How did you finally succeed in establishing photography as an art form in Switzerland?

There were, as I mentioned, many obstacles associated with setting up the gallery. In the first few years, I had to give several lectures, was invited to speak by Service Clubs and showed photographic art to interested audiences at special lunches. I also printed catalogues and organised tours of the gallery with the goal of showing people why photography is an art form and deserves to be taken seriously. Even today, thirty years after the foundation of the gallery, after hundreds of events and more than 140 exhibitions of photographic art, very few people know that to date there have only been two known cases of forgery in photography. This is a stark contrast to painting, where thousands of forgeries are circulating. I’m speaking of classic photography and not of digital photography, where “forgeries” are, of course, possible. If you have, say, a negative of Stieglitz dating back to 1921, you cannot simply reprint it in a lab and sell it as an original. Experts would immediately recognise the picture as being printed today and not an original print. You cannot forge these photos, simply because the ageing process cannot be faked. In addition, the chemical development of those days cannot be reproduced today and the photographers’ own hand-coated paper and the light sources in the laboratory were completely different from today’s equipment. Each photographer used their personal tricks and methods when developing their photos. These „secret recipes“ were guarded jealously, just as the Coca Cola recipe is kept under lock and key.

Dueblin: Many of the best known photographic artists come from Europe, where the first attempts at photography were made in 1826, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, for example.Even so, as has been mentioned, photographic art only became accepted in Europe decades after it was established in the USA.

That’s correct and quite a paradox. Many of the great photographers are Europeans. These, however, were discovered in the USA. Over the last few decades, I have tried to bring these icons back to Europe. Some of them lived in the USA as it was the only place where there was any serious interest in photography. Their photos were sold there in galleries and exhibited in museums. There were quite a number of attempts to introduce photography as an art form in Europe. Nadar, alias Gaspard-Felix Tournachon, for example, was photographed as he flew over Paris in a hot air balloon. In 1896 Daumier wrote the caption: “Nadar, élévant la photographie à la hauteur de l’Art.“ (“Nadar has elevated photography to the level of art.”) These early attempts to establish photographic art failed, however, because of the very conservative understanding of the concept of art. Later attempts were made with Pictorialism. This was another gimmick by photographers frustrated by the lack of respect for their art. By linking photography with painting, they sought to present photography as an art. The photographs were processed in a painterly way, softened in the laboratory and made loose and warm. Pictorial photographs are similar to paintings. Works of that style today are much sought after by collectors and fetch high prices. However, Pictorialism failed in the same way as photography, relegated to a niche existence in exhibitions.

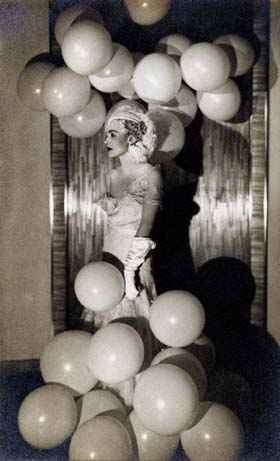

Man Ray: „Countess Celani at the Bal Blanc“, ca. 1930, Vintage gelatin silver print (c) Galerie zur Stockeregg, Zürich, Kaspar M. Fleischmann

Dueblin: Many of the most renowned photographers were also painters. I am thinking, for example, of Man Ray and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Was there something special about these photographers?

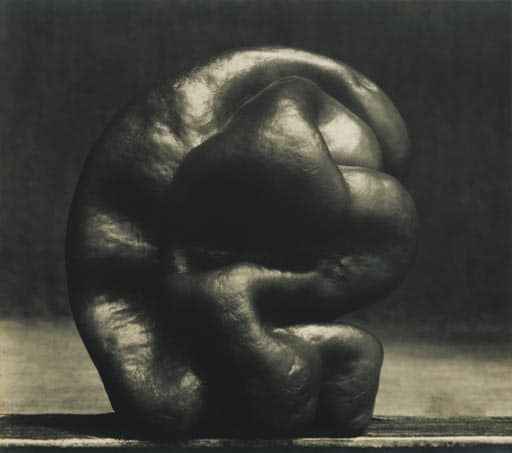

That’s difficult to say and has no simple answer. Brancusi is a good example of an artist who was active in both fine arts and photography. He was a sculptor and photographer. His photographic art is only interesting if you know why he took photos. He did so only because he thought that you could look at his sculptures from many different angles, but that only one perspective was true and valid. Thanks to photography, he was able to show and capture this single correct standpoint for looking at his sculptures. He, therefore, immersed himself in photography and is one of the most exceptional photographers in the world today.

Dorothea Lange once said that it is not by chance that a photographer becomes a photographer, in the same way that it is not by chance that a lion tamer becomes a lion tamer. What do you think are the reasons a person chooses photography as an art and what distinguishes photographic artists from the many hobby photographers?

Every artist searches for expression. The basic principle is: every impression seeks expression. Most people feel an inner tension that they would like to release, for example through physical and/or creative activity. This tension is often stronger and more specific in artists than in other people. Photography is kind of a valve which can reduce this inner pressure. The photographer wants to express what he or she sees through an artistic act: photography. We have to differentiate between looking at something and seeing something. 99% of people look at something. 1% see something. Exceptional photographers see. They usually have to work under conditions that they cannot neither change nor influence. They can only see them. Seeing well is both a mental and emotional action and requires a vision. Very good photographers are able to intellectually transpose their emotional world and their surrounding material world into a vision.

Dueblin: You have described that beautifully, but did not mention technology. Some photographers have made incredible photographs with very basic equipment, for instance Edward Henry Weston. What role does technology play in photography?

You are correct. One says: the important thing is the person behind the equipment, not the equipment in front of the person. This is a fundamental statement. It also holds true for Edward Weston. Some of the most renowned photographers have made their best photographs with quite mediocre technical resources. Very good photographers already see the picture they want to take in their minds. They then have to take the right actions in order to shoot it. Everything must fit, from the correct lighting on site, to the chemistry used for the prints. Art photographers will only take the photo when they are certain that all the external conditions for the picture they have in their heads have been met. Then, what follows in the laboratory is the critical interpretation of the negative and its realisation through the artist’s hands. This sets them apart from hobby photographers and, naturally, therein also lies a critical difference to digital photography.

Edward Weston, „Pepper“, 1929, Vintage gelatin silver print (c) Galerie zur Stockeregg, Zürich, Kaspar M. Fleischmann

Dueblin: At some point in the 1970s and 80s, the first small hand-held cameras were sold. Today almost everyone owns a digital camera. I would like to know if, from your perspective, this has an impact on people and society in so far as today you can quickly photograph everything and millions of photos are taken. Will this lead to a shift in consciousness or perception in our society?

This is a huge topic and one that I have been interested in for many years now. In my latest book, which has only just been published, and which deals with 30 years of gallery work, I mentioned that over the next 10 years our task will be to draw a crystal-clear line between the world of digital and analogue photography. The digital world is moving in the direction depicted by the famous physicist Hawkins. He says that everything is becoming faster and simultaneously more complex. Digital photography as it is practised and seen today is about speed and bulk.

Add to this superficiality. Today you search for a good picture among several thousands of photos. Analogue photography, on the other hand, works quite differently. It is about slowness and about a focused, gentle and clean approach to photography. The digital photo appears right in front of you, you can delete it easily and take it again and again if you don’t like it. However with an analogue photo, it’s in the “box”. You will only see if the photo is bad after it is developed in the laboratory. Therefore, analogue photographers are more careful and take their time. These are two completely different approaches. The new one, of course, has an impact on other aspects of life. It changes the quality of our observations and our attitude towards time. The dimensions of the new technology are still not apparent. However it’s like replacing the pencils and brushes for drawing and painting overnight.

Dueblin: Many photographers see themselves as craftsmen rather than artists. Is photography also a craft?

Top level photography takes technical skill and patience and is an artistic act. That hasalways been so and will not change. The best photographers were truly excellent craftsmen. They had to bring something from film to paper. The photos that you see here in this roomare known as ”vintage prints” and are, therefore, quite expensive. A vintage print is made by the photographer personally at the time the negative is developed. The widespread popularity of digigraphy, as I call it in contrast to conventional analogue photography, will bring major changes to the photography scene. In the near future, it could be difficult to buy a roll of film in a shop.

Dueblin: What are your hopes for Switzerland and photography and what would you still like to achieve in terms of photography in the future?

In recent years, I have worked a great deal with the University of Zurich. There, as I have already mentioned, I was able to establish a course of study on the theory and history of photography with the support of the Dr. Carlo Fleischmann foundation. In this regard, I also keep in touch with the Fotomuseum Winterthur and Kunsthaus Zurich, where I was able to demonstrate the importance of photography early on. I would be happy to continue my gallery work and establish a centre for photographic art, culture, science and research here so that Zurich will become a global leader in this field. We are well on our way towards achieving this goal. I am working on allowing students of Zurich University to work with originals. In seminars and workshops they should learn how to handle materials correctly. It is also possible for them to write a dissertation on certain photographic topics as well as study archiving and the care of photographs. I hope that this will develop some momentum that will eventually get both the canton and the country involved. Conditions such as these make studying in Zurich quite attractive today. I hope that my vision will be fully realised, as this would consolidate and establish lasting value for everything I have achieved in relation to photography over the past three decades. I also hope that Switzerland will take a leading position in art, research and in the scientific engagement with photographic art.

Dueblin: Mr. Fleischmann, thank you very much for this conversation. I wish you and your projects continued success in the future.

- Angela Rosengart über ihre Lieblingsmaler Pablo Picasso und Paul Klee sowie über die Geschichte der Galerie Rosengart in Luzern

- Prof. Dr. h.c. mult. Reinhold Würth über die Würth-Gruppe, den Zusammenhang zwischen Kunst und Unternehmertum sowie Europas Zukunft

- Erwin Wurm über sein künstlerisches Schaffen, seine Skulpturen und was man in seiner Kunst zwischen den Zeilen lesen kann

- Bettina Eichin über ihr Leben, ihr Kunstverständnis und ihre Skulpturen

- Ansicht über Impressionismus im Jahr 1883

- Andrea Raschèr – Provenienzforschung früher und heute mit einem Blick auf die Washingtoner Konferenz 1998

______________________________

Links

– Galerie zur Stockeregg