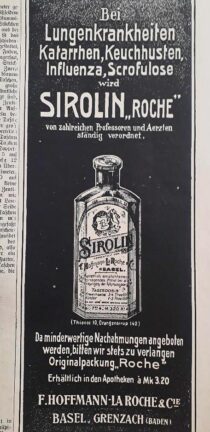

Willard “Sandy” Boothby worked as a Vice-Chairman of the Investment Banking Department of JP Morgan. He is one of the best-known investment bankers, and has worked very closely in his career with the Swiss company Roche, which is just celebrating its 125th anniversary. Boothby graduated from Princeton University and holds an MBA degree from Harvard Business School. Boothby is looking back on an interesting and challenging career in which he dealt with senior management and Boards of Directors of some of the biggest companies on earth, such as with legendary managers from industrial and pharmaceutical companies. He also worked closely with Dr. Fritz Gerber and Dr. Dr. h.c. Henri B. Meier, the top duo of Roche’s recovery strategy, who later bought Genentech, a legendary and sustainable deal that helped Roche to survive and prosper after difficult times, when Roche lost its patent on Valium, its immense blockbuster drug. There was little time to find new business opportunities and new blockbusters back then, but there was only very little money to take over interesting firms. So, Roche, under the financial management of Dr. Dr. h.c. Henri B. Meier, started with financial deals to fill Roche’s cash coffer to be able to act on difficult and uncertain markets, with the help of investment bankers such as Willard Boothby, who had worked for over a decade for Roche. A Xecutives.net interview about the Genentech deal with legendary venture capitalist Frederick “Fred” Frank has been published recently. The interview with legendary Frederick Frank gives a deep insight into the world of Biotech and Venture Capital. But Genentech was not the only company that changed Roche’s position on the market sustainably.

In this interview with Xecutives.net, Mr. Willard Boothby talks about some outstanding deals and about his relationship to Roche, which had an effect on his business career. He discusses the challenges facing investment banks helping and supporting companies all over the world.

Xecutives.net: Mr. Boothby, you can look back at an interesting investment banker stint for JP Morgan, still a powerful bank with a long history. I had the chance to talk with Frederick “Fred” Frank, who unfortunately passed away this September 2021; ours was most probably his last interview. Not only a very talented and very skilled venture capitalist, Frank also possessed this philosophical side which made him a legendary advisor, who helped dozens of start-up companies grow and get successful. You yourself have helped many very big and well-known companies to find the right partners, make the right purchase decisions and help invest money in the financial markets. Given your prominence in the field, I would like to ask you how you came to investment banking.

Willard Boothby: I come from a family of bankers, so from an early age I was exposed to the profession. At business school I decided that if I was going into banking, I wanted to work where the job would involve a mix of sales and analysis. Investment banking provided that opportunity. I retired early in part due to discomfiting changes in clients’ perceptions that occurred towards the end of my career. Clients became jaded by the “success fee” compensation model. It caused them to question whether the advice was truly disinterested. A related source of cynicism about the advice being proffered derived from concern that bankers/firms were short-term oriented. That they don’t focus on the long-term best interests of their clients, and that they can be quick to jilt long-term relationships. I led some major transactions in the pharmaceutical and other industries. My work with Roche and especially Dr. Dr. h.c. Henri B. Meier was certainly the highlight of my career.

Xecutives.net: Henri B. Henri B. Meier and his team obviously made the right decisions and earned Roche a lot of money. Many people back then called the company a bank, the „Roche-Bank“. How did Roche make these decisions, and what did it take to carry out these effective decisions? Was this also a matter of chance, or did Roche and its CFO go to the right investment banker able to assess the market correctly?

Willard Boothby: As Fred stated, Fritz Gerber relied very much on Henri. You correctly cited Henri’s success with alternative investments, but what I remember best is the spirited way he policed at Roche what he deemed excess spending, fueled by the favorable pharma margins. On acquisitions Henri was quick to adopt creative structures. On the Genentech acquisition the embedded puts and calls afforded a way to bridge the control Roche wanted with the autonomy Genentech wanted – and perhaps needed to preserve its R&D culture. We were involved with the Genentech acquisition; and after the acquisition worked with Henri on exercising the embedded calls and on reissuing non-option shares Henri recognized that the market price of the options embedded Genentech shares due to the calls, was artificially depressed, offering an attractive arbitrage. It was an immensely profitable “trade”. JPM did not structure nor did it underwrite any of Roche’s structured financial issuances, with the exception of the put/call options embedded Genentech transaction. On the Syntex acquisition, Henri embraced a preferred stock structure that created a tax deferral for part of the Allen family investors.

Xecutives.net: Lots of interview partners have talked about mergers and big takeovers. Two legendary deals were Boehringer Mannheim and Genentech. The latter possibly saved Roche’s existence. However, for Roche the risk was worth it; the firm accrued big business with Genentech. Do you see distinct patterns when companies take over others? Is there some kind of recipe that you yourself have followed when selling companies to other companies and taking care of the financial issues in acquisitions and mergers?

Willard Boothby: Generally, mergers and acquisitions offer an avenue for growth, though not without risk. Growth can result from increased scale and/or synergies. The risk derives from potentially over-paying, failure to integrate and cultural incompatibility.

Xecutives.net: That’s right, not all take-over situations were successful for some companies. When Roche wanted to take over a pharmaceutical company in USA and Kodak had paid a higher price, a higher price was rejected back then by Fritz Gerber and Henri B. Meier. Kodak ran into major problems, which could have led to the company’s demise much earlier than when it transpired later on. What was the reason for Kodak to enter a business field about which the photography company had very little experience or first-hand knowledge?

Willard Boothby: With the Sterling Drug acquisition Kodak came into the process as a “white knight” only to overpay, animated by a desperation to diversify away from the photography business.

Xecutives.net: Frederick Frank was very open about his personal relationship to money. Earning and later investing and multiplying money represented to him securing a comfortable life for his family; and he specifically gave away money as a philanthropist to what he thought were worthy causes, mostly associated with educational and scientific institutions he’d been associated as an alumnus or a colleague. Americans look back on a long eleemosynary tradition of donating money to charitable causes; I’ve been told your wife, Linda, is a vigorous proponent within this tradition as well. There are certainly tax reasons for this, but in the USA this giving and spending and supporting other people with less money has a completely different dimension. Often, rich people donate money to the schools and universities they’ve attended. Fortified by these funds, this money, which are not infrequently spent on venture capital projects, American universities also create great value. Charitable contributions function quite differently in Europe, not on this vastly generous American scale. What do you think are the reasons for this?

Willard Boothby: Why the US has a tradition of philanthropy is a question that I have puzzled over for many years. Tax advantages explain part of the answer. I think also in the US the value of charitable gifts is generally publicized. Many successful people seek public recognition of their success and the approval that comes from being seen to be doing “good works”. Also, the gifts can provide a path to sitting on a charity’s board which in turn can afford an opportunity to network.

Xecutives.net: Europe, especially wealthy Switzerland, has a very difficult time coming up with, and justifying the outlay of, venture capital. This is also attested to by interview partners such as Prof. Dr. Heinz Riesenhuber, ex Minister of Helmut Kohl in Germany, Henri B. Meier, as well as from Frederick Frank, who spoke very clearly about the problem of value creation. You are not a venture capitalist, but you are an expert regarding financial conditions of companies and their markets. Where do you think venture capital makes sense in European markets?

Willard Boothby: You ask about venture capital’s necessary inputs. Importantly, there can be no stigma for failure. On the upside there should be an opportunity to make a huge amount of money. Finally, society must celebrate the individual over the corporate cog. Those investing in venture businesses are generally well-advised to create a portfolio of venture investments.

Xecutives.net: Investment bankers don’t always have it easy–their reputation has been tarnished in recent years. Hollywood movies cynically feature them as villains, for instance the ruthless portrait of such a figure by Hollywood star Leonardo di Caprio in the movie “The Wolf of Wall Street”. This has led to the banking business being seen in a negative light by many people as a cutthroat business. What are the reasons that banks are suffering from image damage today? Surely there are plenty of other industries to criticize! I mention this because Credit Suisse is currently also embroiled in a major crisis, for which many people have scant understanding.

Willard Boothby: You’re right with your perception; the investment banking business hardly enjoys a monopoly on questionable conduct. Today’s papers offer many examples of companies that have derailed due to illegal and or moral missteps, e.g., Theranos and Facebook. Earlier VW ran aground in the catalytic converter debacle and GM in connection with airbags. You referenced Credit Suisse, its Greensill and Archegos involvements. While I am not knowledgeable as to exactly what transpired in these two instances, what is typical is that greed or incompetence causes a firm to take on too much risk, and then often there ensues an effort to downplay, or worse, cover up the resultant mess.

Xecutives.net: You started providing financial advice and support to Roche in the 1980s, and at that time met with the company’s then chief financial officer, Henri B. Meier. How do you remember Roche, a company that is now 125 years old, back then?

Willard Boothby: Apropos Roche through the ages, my window is a narrow one as I retired in 2004. During my years working with Roche, I was always impressed with Henri’s entrepreneurial bent and energetic approach to life. He combined a risk-taking spirit with a commitment to long-term sustainability. With the signal Genentech acquisition and his other contributions, Henri truly left a valuable legacy.

Xecutives.net: When I asked Frederick Frank about the roles of the top management duo back then, Henri B. Meier and Fritz Gerber, he said: “That’s a very good question. It was very unusual because Fritz Gerber totally depended on Henri from the financial point of view. And what people don’t realize is that during this period Roche was actually having some financial challenges. The reason Roche continued to show growth and earnings is because Henri was investing in public companies with all Roche’s excess cash. Henri was a very astute investor and made a lot of money. He made more money on investments than Roche made in the pharmaceutical sector.” What was your impression back then of the Roche management and its leaders?

Willard Boothby: When you say “investing” do you mean alternative investments, or investments in acquisitions, presumably not investments in the core business? I know that Henri was very aggressive and successful in investing excess cash in alternative investments, but I had almost no involvement in that activity, though once we did make a trip together to inspect some Florida land as a possible investment. I have often said that Henri is ‘his own man’. By that term I meant to capture the fact that Henri seemed to operate within Roche with almost complete autonomy, and that vis à vis the financial community he often opted to defy received wisdom.

Xecutives.net: It was clear to the Roche management back then that investments must result in value creation. This is a big issue that Henri B. Meier and others with his “Pro Zukunftsfonds Schweiz” today, a vehicle that creates opportunities to invest Swiss savings from the collective savings pot in Switzerland, instantiating economic gains at the forefront of technical progress. What role did value creation play back then–when it wasn’t a matter of bets or options, when it was not only about filling the cash box?

Willard Boothby: With respect to value creation, one good example is the Genentech acquisition where there was a prescient perception that the Genentech scientists were some of the world’s best and that their creativity would pay huge dividends. Generally, I would say venture investment is no different from any other investing, to wit, a weighing of risk and return. Henri limited the risk by carefully measuring the upfront investment. With astute due diligence he was able to arrive at reasonable estimates of the cash flow returns and what future developments could conceivably derail the expected returns. Judgment and foresight allowed Henri to enjoy a storied career as an astute investor.

Xecutives.net: What skills does an investment banker require to be able to advise companies like Roche, but also other companies around the world?

Willard Boothby: I think the ideal investment banker is one who possesses and can project integrity, intelligence, sophistication, and charm.

Xecutives.net: Mr. Boothby, thank you very much for your time spent giving this interview. I wish you and your family health and further success regarding your projects.

© 2021 by Christian Dueblin. All rights reserved. Other publications are only allowed with the explicit permission of the author.

More interviews that you may find interesting (in German or English):

- Dr. Dr. h.c. Henri B. Meier über die Wirtschaft und die Probleme bei der Beschaffung von Risiko- und Wagniskapital

- Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Heinz Riesenhuber über seinen Werdegang und den dringend nötigen Kulturwandel in der Wirtschaft

- Frederick Frank(†) – a venture capital specialist who has never lost his philosophical streak

- Samuel S. Weber – about money, investing, gold and the drifting apart of the financial and real economy

- Prof. Dr. h.c. mult. Reinhold Würth über die Würth-Gruppe, den Zusammenhang zwischen Kunst und Unternehmertum sowie Europas Zukunft

- Klaus Endress über über seinen Werdegang, seine Lebensphilosophie und seine Einstellung zu Geld und Macht